Three Great Reads For the Lunar New Year

“Invitation to A Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food”

Settle into your favorite chair and prepare to get hungry as you immerse yourself in “Invitation to A Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food” (W.W. Norton & Co., 2023).

London-based Fuchsia Dunlop has long been one of my favorite writers — and speakers. The first Westerner to train as a chef at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine, she is fluent in speaking, writing, and reading Chinese. Her knowledge of the foods of every region in China is bar none.

In her newest book, of which I received a review copy, the four-time James Beard Award-winning cookbook author explores the historical, philosophical, and technical aspects of the vast range of Chinese food by presenting a literary banquet of 30 dishes. Each chapter hones in on one particular regional dish, serving up not only its origins and the importance of its ingredients, but the food producers, farmers, chefs, and home cooks who have put their indelible stamp on it.

For instance, what cut of pork do the Chinese prefer? Dunlop writes: “To Chinese palates, the best parts of the pig are those laced with luscious fat and skin, which are nuo (huggy and sticky and glutinous, like snouts and trotters) and yourun (juicy with oil). Above all, when well cooked, they are fei or bu ni — richly fat without being greasy. Nothing, really, is better than pork belly, with its luxurious layers of skin, fat and flesh…The least interesting parts are the ones that the English traditionally prefer, with uniform lean meat…A grilled pork chop, English style, especially when shorn of fat, has a texture the Chinese tend to describe as ‘firewood.’ (chai)”

You’ll be wishing this book came with smell-a-vision.

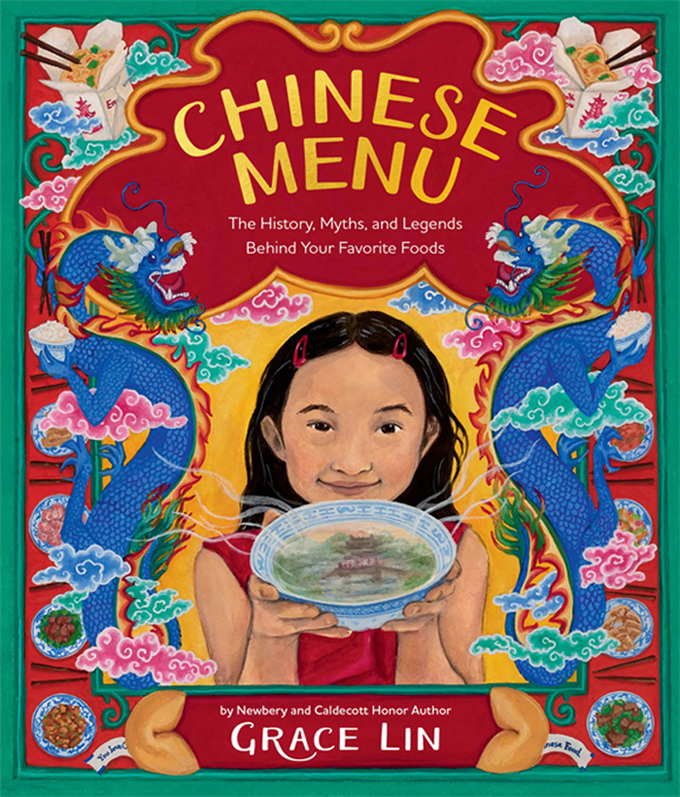

“Chinese Menu”

Massachusetts-based author and illustrator Grace Lin may be known for her children’s books, for which she won the Children’s Literature Legacy Award. But her newest book, “Chinese Menu” (Little, Brown and Company, 2023), of which I received a review copy, is sure to delight readers of all ages and engage absolutely anyone who loves Chinese food.

In this book, she writes about the customs, facts, and folklore tales behind a variety of favorite Chinese foodstuffs and dishes, from tea to dumplings and sizzling rice soup to Kung Pao chicken, mapo tofu, and fortune cookies.

Her beautiful full-color illustrations bring everything to life, too.

Did you know that Chinese emperors used silver chopsticks because they believed they would react and turn black if their food was poisoned? Or that there’s a myth that the scallion pancake inspired Italian pizza? Or that tofu originated in China more than 2,000 years ago?

Moreover, why are oranges so appreciated? Oranges represent good fortune, Lin writes, “The brilliant color denotes happiness, and its roundness signifies wholeness and unity. But even more so, the word for orange in Chinese is a homophone. When one says the word orange (cheng) in Mandarin, it also sounds like the word for success (cheng), while the word for large tangerine (ji) sounds like the word for luck (juzi). In Cantonese, the world for orange (or large tangerine) is pronounced gansi, which sounds like how one would say the word ‘gold’ (garnzi). So, when a restaurant offers you slices of oranges, they are not just giving you a refreshing end to your meal, but they are thanking you with a wish of good luck and gold!”

“Everything I Learned, I Learned In A Chinese Restaurant”

Curtis Chin, a filmmaker, writer and activist, has crafted an enthralling memoir with his “Everything I Learned, I Learned In A Chinese Restaurant” (Little, Brown and Company, 2023), of which I received a review copy.

A co-founder of the Asian American Writers Workshop in New York City, he has written for network television before transitioning to social-justice documentaries. In this book, he recounts his life growing up in his family’s Chung’s Cantonese Cuisine, which his family opened originally in 1940 in Detroit’s Chinatown.

It was founded by his great-great grandfather, who immigrated to the United States to escape the Opium Wars. He settled in Detroit, hoping to find work. He did, but only in a laundry. Scrimping and saving over long hours, he managed to save enough to open a dry goods store, then eventually the restaurant. It proved popular from the start, drawing people of all races during a still volatile time in history, to enjoy chow mein, chop suey, and egg foo young.

As Chin recounts coming of age as a gay American-born-Chinese against this backdrop, there is poignancy, humor, and plenty of straight talk about the times. For instance, he recounts that when his family, who originally lived above the restaurant, sought to move to a larger abode in the suburbs, the white developer refused to sell to them. One of the restaurant’s Jewish customers took it upon himself to buy the land and sell it to the family at cost. The family was so grateful that they gave him free egg rolls for life.

Writing in the forward, he says, “The important lessons that guided me through my childhood came served like a big Chinese banquet, from the highs of cooking with my mom and dad to the lows of waiting on some of the rudest customers; a chorus of sweet and sour, salty and savory, sugary and spicy flavors that counseled me toward a well-led and well-fed, life.”

Indeed, take a deep dive into this book, and you’ll find yourself satiated in more ways than you’d expect.

I know a certain special soon-to-be-ten-years-old little boy who not only loves to eat, and read, and cook, but also loves to draw. He has a birthday coming up. You can be sure I’m ordering the Chinese Menu book as soon as I finish typing this comment. Looking through the Amazon listing just now I can see that he will be, dare I say, drawn to the illustrations as much as the content. Thanks for another influential post, Carolyn!

Hi Carroll: The “Chinese Menu” book would be perfect for your food-loving grandson. You’ll have to tell me his reaction when he opens it up on his birthday.