You can almost feel it in the air, can’t you? A little more sunshine peeking through, a little more daylight lingering at the end of the day. Yes, spring is on its way. And you know what that means?

Time for planting, of course. Yes, even for those with not-so-green thumbs like myself, this is the time to start thinking about the wondrous possibilities that we can nurture in our very own little window pots or in raised beds in the backyard.

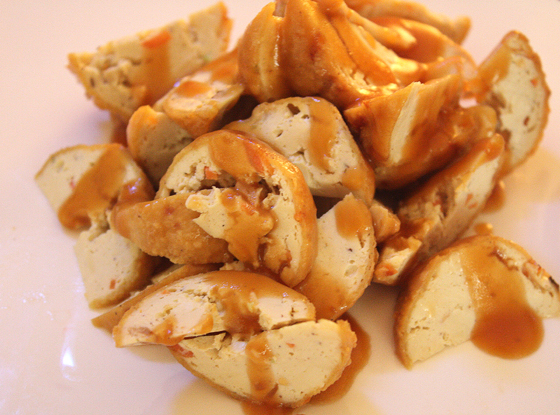

To entice you further, the kind folks at the Cook’s Garden, a gourmet retailer of vegetables, lettuces and herbs, is allowing me to do a great give-away: Three winners will receive the seeds necessary to grow most everything in that colorful salad shown above. (OK, except for the cheese and olive oil, you wise guys.) Not only that, each winner also will receive a beautiful artisan oval cutting board to cut all those home-grown veggies on.

Call it the ultimate do-it-yourself salad when you grow the Myway Arugula, Lettuce Baby Red Mix, Tomato Persimmon and Tomato Carmelita, all by yourself.

When harvest time rolls around, slice the tomatoes about 3/8-inch thick, and alternate them in a row on a serving dish. Layer Myway Arugula and Lettuce Baby Red Mix over the top. Next, add slices of your favorite cheese over the top. Finally, whisk together olive oil, crushed garlic, dill, chives, salt, pepper, wine vinegar and dry mustard to taste. Drizzle over salad, and enjoy.

Here’s how to score those seeds and cutting board: Name the fruit, vegetable or herb that’s most like your personality, and why. Enter the contest by the end of the day, March 13. The three most clever or memorable responses will win. Contest results will be announced on March 15. Participants must reside in the continental United States.

To get you started here’s my own response: Kabocha squash. It’s Asian like me, as well as a little sweet, very versatile, and distinctive. It’s resilient — you can buy it, stick it on the counter, and it’ll keep just fine for quite a spell all to its self. It’s a bit starchy, too — and I never met a carb I didn’t like.

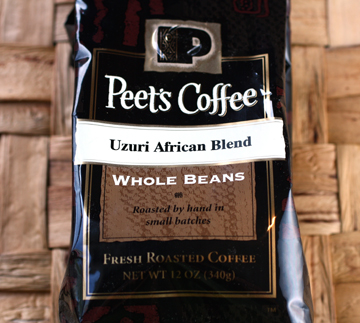

And without further adieu, here are the five winners of the last contest, who will each receive a bag of the new Peet’s Uzuri African Blend coffee:

Read more