Harmony and Simplicity Meet at Hachi Ju Hachi in Saratoga

At Hachi Ju Hachi, the Japanese restaurant in downtown Saratoga, you won’t find the standard menu of teriyaki, Philly rolls, and Bento Box “A”’s like that of so many other establishments. Nor will you find bells, whistles, over-the-top flourishes or modern sensibilities that jar and shock.

Instead, you will find dishes with a real purity of flavor and lovely simplicity.

Chef-Owner Jin Suzuki may be only 45 years old, but he is decidedly old-school when it comes to cooking.

At 19, he started his training as a chef at a restaurant just outside of Tokyo. For six months, all he did was clean the windows and floors. He wasn’t even allowed to step foot inside the kitchen to wash dishes. It would be another three years before he was allowed to wash the rice. All of this had a profound effect on him.

“The more I saw, the more I got curious,” he says. “I learned that in-between confidence and arrogance is humility. So many chefs can be good technically. But so few chefs can attain spirituality in their cooking.”

One need only glimpse Suzuki, with his crisp chef’s coat, perfectly knotted tie, geta sandals, and serene composure to know this is a chef who has indeed attained that.

The name of the restaurant, Hachi Ju Hachi, which opened in November, comes from the word for “rice” in Japanese. Taken apart, the kanji characters represent the number,”88.” Whether it was fate or not that led Suzuki to this exact location to open his restaurant is anyone’s guess. All he knows is that a few months after he opened, he happened to notice that the sidewalk tree right in front of his restaurant bears an identification medallion with “88” engraved on it. Coincidence? Or not?

Suzuki likes to believe it was destiny that led him to Saratoga, where he practices his version of washoku: traditional Japanese food based on the principles of harmony, balance, simplicity and restraint.

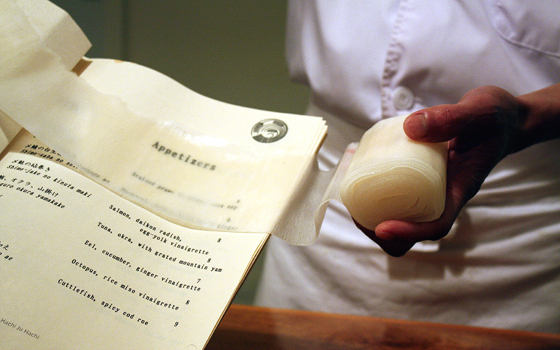

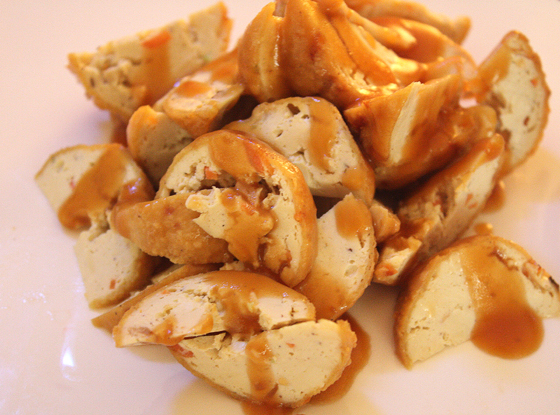

He practices techniques that form the basis of the art of kaiseki (Japanese haute cuisine), some of which are not even done in Japan anymore because they are so time-consuming to do, he says. This is a man who makes his own salt by boiling iodized salt and sea salt in water for six hours until the liquid evaporates and all that is left is a softer, milder alchemy with an almost faint sweetness. He preserves shiitake mushrooms by braising them in sake, soy and kombu until they are soft, sticky and almost candy-like. Suzuki also makes his own miso with shrimp heads that he’s fermented for six months, as well as homemade tofu using white sesame, black sesame, edamame and corn.

“When I learned how to make tofu properly, it moved my soul,” he says. “I kid you not.

Although the restaurant has a few tables, most of the seats — and the best ones — are at the shiny, blond bar that has a view of the kitchen. A kids’ playroom, complete with all manner of toys, is at the back of the restaurant for diners’ children, as well as Suzuki’s 4-year-old daughter, who sometimes helps deliver menus to patrons.