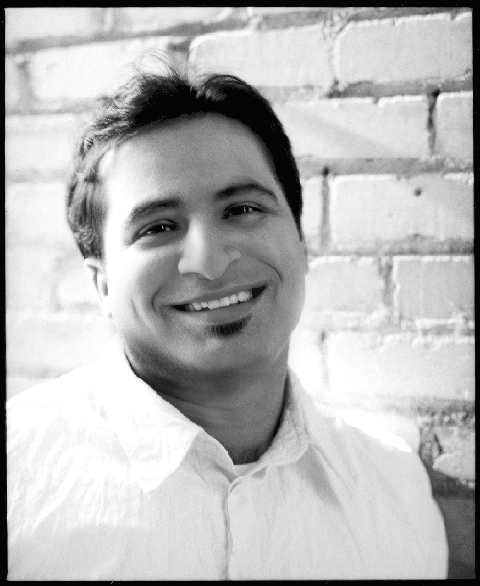

Take Five with “Top Chef Masters” Contender Suvir Saran, on His Upcoming Bay Area Appearance with the Food Gal

If you’ve been tuning in to this season’s “Top Chef Masters” on Bravo TV, you’ve probably already discovered not only how charismatic, but candid Chef Suvir Saran can be.

The 38-year-old, executive chef/owner of award-winning Devi in New York City will tell you he’s probably one of the most frank chefs you’ll ever meet. (Wait till you hear what he thinks of Zagat and Yelp.) That forthrightness, coupled with an energetic and telegenic presence, has made him a favorite speaker at seminars. See for yourself when he joins yours truly on stage at 7 p.m. April 29 for a lively Q&A session at the India Community Center in Milpitas. Tickets are $50 for ICC members; and $55 for non-members. Executive Chef Vittal Shetty of Amber India in San Jose will prepare signature hors d’oeuvres inspired by Saran’s recipes.

Saran’s South Bay appearance will be in conjunction with “Dining Out for Life Silicon Valley,” which is part of an annual national campaign, in which participating restaurants raise money for those living with HIV/AIDS. Proceeds from the Silicon Valley event will support the Health Trust AIDS Services, which helps more than 800 people in Santa Clara County with hot meal delivery, food baskets, and housing assistance.

Forty restaurants in 12 Silicon Valley cities will donate at least 25 percent of their food sales on April 28 to that organization. For more details, click here. Saran also will be making a surprise appearance that evening at four South Bay restaurants, so keep your eyes peeled.

Additionally, at 12:30 p.m. April 29, Saran will present a talk about healthy cooking at the Health Trust Food Basket in San Jose. He will be joined by cookbook author and legendary restaurateur, Joyce Goldstein, who was an early pioneer in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Advance reservations are required by emailing Jon Breen at jonb@healthtrust.org.

Lastly, Saran is not only donating four dinners for two at Devi, but also donating his time to cook a meal for eight at a private home in the Bay Area. These items will be auctioned off online on the Health Trusts Web site to the highest bidders, starting at midnight May 5.

Last week, I had a chance to chat by phone with him about what brought him to the United States at age 20, and what he thinks of the state of Indian food here.

Q: Why is ‘Dining Out for Life’ a cause near and dear to you?

A: I lost many friends to HIV/AIDS. My partner of nine years is a big civil rights person. He’s always yelling and screaming, and I realized that a voice demanding humanity was important in American society.

Most people take it for granted that we live in a democracy and everything is perfect. I have to be a champion of underdogs. I owe it to every underdog to speak up for them.

Q: Devi was the first and only Indian restaurant in the United States to earn a Michelin star. What did that honor mean to you?

A: That I should commit suicide now that they’ve taken it away after two years. (laughs) It was an honor. It was a wonderful thing. We got it at the top of our game. Then, it was taken from us. Since my business partner and I had a separation, we are now back at our prime. Who knows? Maybe next year, we’ll get it back again.

We had it two years in a row. It was a luxury. I don’t take it for granted. I look it as a sweet gift bestowed us on by powers that be. It’s not like those worthless Zagat ratings, which have no value in my mind.

Q: I’m almost afraid to ask what you think of Yelp?